Article from Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Thanks to JOSHUA AXELROD

“I thank the Negro League players for their fortitude, strength, wisdom, the enjoyment they gave fans all over the country,” Oliver said Thursday night. “Because, I’ll be honest with you, I could not have done it.”

- Al Oliver

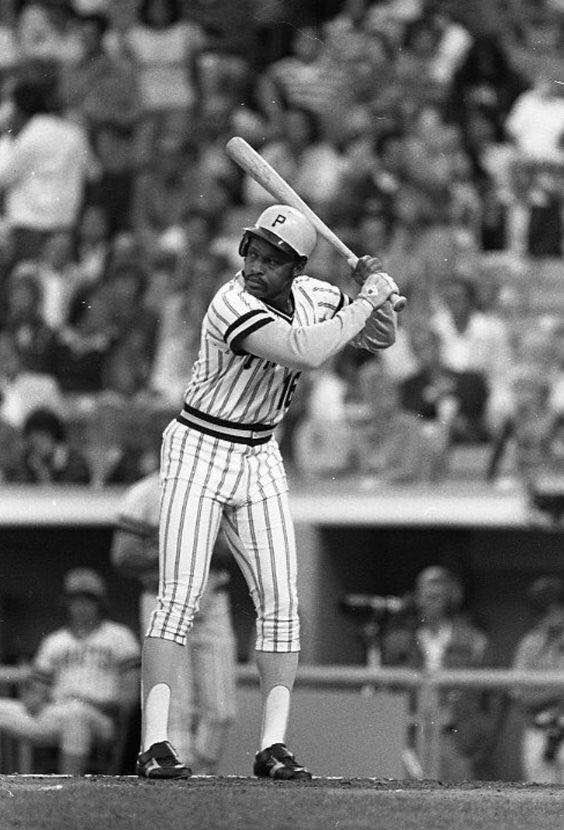

Al Oliver remembers exactly where he was when he realized he was playing for the first all-black starting lineup in MLB history.

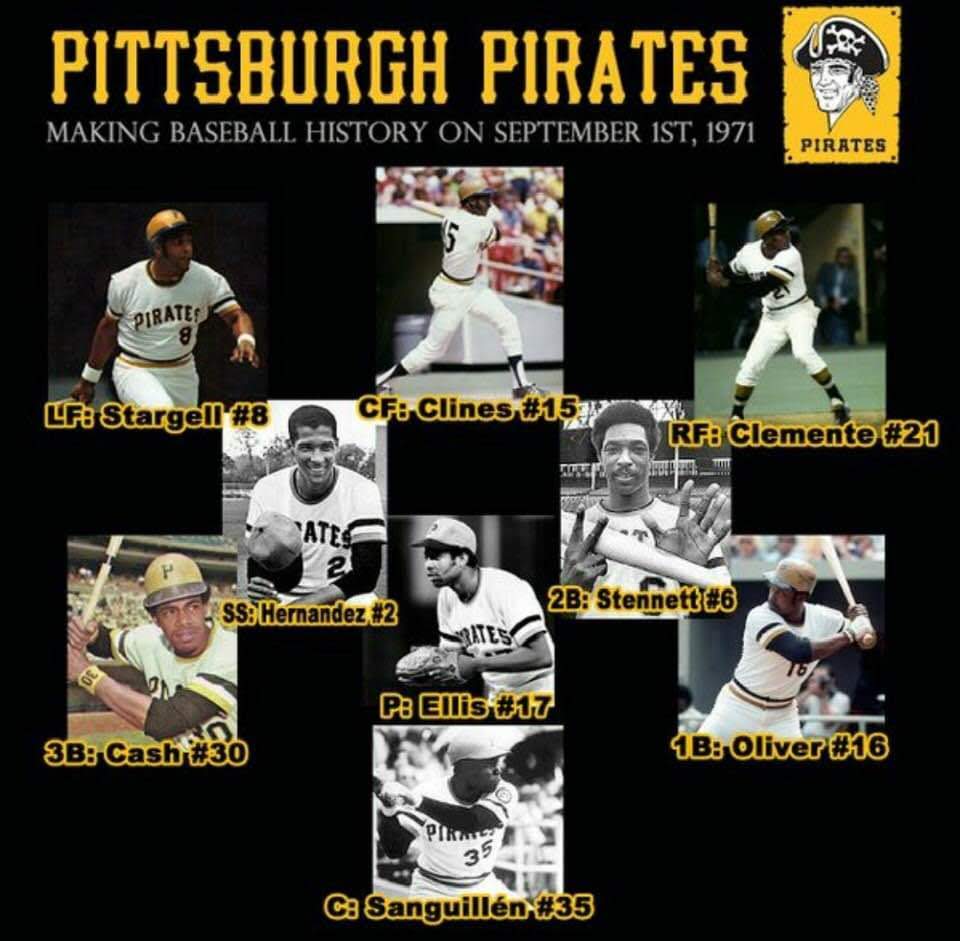

It was Sept. 1, 1971. The Pirates were playing the Phillies at Three Rivers Stadium, and Oliver — who played for the Pirates from 1968-77 — was on first base. At some point in the fourth inning, he had a revelation that inspired him to tell third baseman Dave Cash, “You know what? We’ve got nine brothers out there. Ain’t that something.”

Oliver is keenly aware that he might never have even made it to the major leagues, let alone become a part of an all-black starting lineup that won the 1971 World Series, if not for the baseball pioneers in the Negro Leagues who helped pave the way for baseball’s eventual integration.

“I thank the Negro League players for their fortitude, strength, wisdom, the enjoyment they gave fans all over the country,” Oliver said Thursday night. “Because, I’ll be honest with you, I could not have done it.”

The Negro Leagues were founded on Feb. 13, 1920, by Andrew “Rube” Foster. On the 100th anniversary of the league’s inception, baseball fans flocked to the Heinz History Center in the Strip District for the “Pittsburgh Negro League Baseball Centennial Commemoration,” a celebration of all that organization accomplished and its local ties, aka the Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords.

The event included a panel moderated by Pirates broadcaster Joe Block and featuring Oliver; Sean Gibson, Grays and Crawfords legend Josh Gibson’s great-grandson; Rob Ruck, a Pitt history professor and author of “Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game”; Samuel W. Black, director of the African American Program at the Heinz History Center; and Charlene Foggie-Barnett, a Teenie Harris archive specialist with the Carnegie Museum of Art.

“This is a sports town,” Gibson said. “Pittsburgh has always been a sports town. We have great teams. What I like the best is they don’t forget about the Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords and have included them in their sport history.”

Black and Ruck helped contextualize the circumstances in the U.S. when the Negro Leagues were founded, which included the popular belief that black players just simply were not as talented at baseball as their white counterparts.

Ruck explained that the Negro Leagues not only helped prove otherwise, but scrimmages between Negro League and white teams helped expose a wider audience to these gifted athletes.

“They’re unifying the community, they’re giving people a collective sense of self-esteem and they’re bridging that racial gap,” he said. “... And they’re doing all this despite segregation.”

As Black pointed out, blacks had been playing baseball since the 1850s. The Negro Leagues just gave them the opportunity to play the sport they loved and assert their place in society.

“We are Americans, too, and this is one way we are going to express that,” he said of the league’s impact.

Though everyone agreed great progress has been since the Negro Leagues were founded, Gibson still bemoaned the lack of diversity in MLB front offices and made it clear that the work his great-grandfather helped kick-start is far from finished.

“Here we are celebrating the Negro Leagues’ 100th anniversary, and we’re still talking about some of the same things my grandfather went through 70 years ago,” Gibson said. “So, until all of us become one and do better, we’ll still be talking about this 24 years later.”

Joshua Axelrod: jaxelrod@post-gazette.com and Twitter @jaxel222